Stencil

Introduction

Hey there! In this post, we’ll start by introducing the stencil operation, covering its background, basic algorithm, and a series of optimization techniques such as shared memory tiling for stencil sweeps, thread coarsening, and register tiling. Stencils are used to solve partial differential equations (PDEs) in applications such as fluid dynamics, heat conductors, weather forecasting, electromagnetics, etc. They process discrete data. They are similar to convolutions; hence, we’ll deal with halo cells and ghost cells here. However, unlike convolutions, stencils solve continuous differentiable functions within the given domain.

This post focuses on the computation pattern where the stencil is applied to the input grid points and produces the output values at all grid points. This is known as stencil sweep.

This blog post is written while reading the eighth chapter, Stencil, of the incredible book “Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach1” by Wen-mei W. Hwu, David B. Kirk, and Izzat El Hajj.

Background

The first step is to convert the continuous functions into a discrete function to process further in the computers. Structured grids are mainly used for the finite difference method to find the derivative of a variable and unstructured grids are used in finite-element and finite-volume methods and are more complex. To derive the approximate value of the discrete function for the x, we need to use the interpolation technique, which we solve using a partial differential equation via stencil.

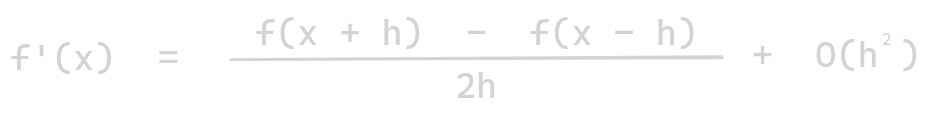

Mathematically, stencils are geometric patterns of weights applied at each point of a grid, which are used to calculate the solutions of the partial differential equations. For example, to calculate the derivative of a one-dimensional function f(x), we discretized into a 1D grid array F. To calculate the finite difference approximation for the first derivative f’(x) is given by:

Parallel stencil: a basic algorithm

This section presents the basic kernel for stencil sweep. We assume that the boundary grid points are not responsible for any change from input to output. It also assumes that each thread block is responsible for calculating the tile of output grid values and that each thread is assigned to one of the output grid points. The kernel below assumes a 3D grid and a 3D seven-point stencil. Here, each thread performs 13 floating-point operations. It’ll take 4 bytes to load each floating point. Therefore, FLOPS is 13 / (7 * 40) = 0.46 OP/B.

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float* in, float* out, unsigned int N) {

unsigned int i = blockIdx.z * blockDim.z + threadIdx.z;

unsigned int j = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y;

unsigned int k = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

// c0-c6: values we get from solving the differential equations.

if (i >= 1 && i < N - 1 && j >= 1 && j < N - 1 && k >= 1 && k < N - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0 * in[i*N*N + j*N + k]

+ c1 * in[i*N*N + j*N + (k - 1)]

+ c2 * in[i*N*N + j*N + (k + 1)]

+ c3 * in[i*N*N + (j - 1)*N + k]

+ c4 * in[i*N*N + (j + 1)*N + k]

+ c5 * in[(i - 1)*N*N + j*N + k]

+ c6 * in[(i + 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

}

Shared Memory tiling for stencil sweep

Shared memory tiling for a stencil is almost the same as that of convolutions, except they do not include the corner grid points (this property is essential for register tiling).

Let’s calculate the FLOPs. Let the input tile be a cube with T grid points in each dimension; hence, T - 2 will be the output grid points. Therefore, each block will have (T - 2)3 active threads calculating the output grid point values. Therefore, the number of operations performed is given by 13 * (T - 2)3 (note 13 here is the number of floating-point arithmetic operations). FLOPS is given by (13 * (T - 2)3) / (4 * T3) OP/B. More input grid point values are reused if the T value is larger.

// In this kernel, blocks are the same size as the input tiles

// and some threads are turned off while calculating the output tiles

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float* in, float* out, unsigned int N) {

// -1 because it assumes a 3D seven-point stencil with one grid point on each side

int i = blockIdx.z * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.z - 1;

int j = blockIdx.y * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.y - 1;

int k = blockIdx.x * OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.x - 1;

__shared__ float in_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

// Every thread loads one grid point

// ghost cells conditions:

// To guard against out of bound access

if (i >= 0 && i < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

in_s[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[i*N*N + j*N + k];

}

__syncthreads();

// each blocks calculating the output tiles

if (i >= 1 && i < N - 1 && j >= 1 && j < N - 1 && k >= 1 && k < N - 1) {

if (threadIdx.z >= 1 && threadIdx.z < IN_TILE_DIM - 1 && threadIdx.y >= 1

&& threadIdx.y < IN_TILE_DIM - 1 && threadIdx.x >= 1 && threadIdx.x < IN_TILE_DIM - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0 * in_s[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c1 * in_s[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x-1]

+ c2 * in_s[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x+1]

+ c3 * in_s[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y-1][threadIdx.x]

+ c4 * in_s[threadIdx.z][threadIdx.y+1][threadIdx.x]

+ c5 * in_s[threadIdx.z-1][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c6 * in_s[threadIdx.z+1][threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

}

The main disadvantages of a small limit on the T value are:

- It limits the compute-to-memory access ratio. This ratio decreases as the T value decreases because of halo overhead. When the data reuse ratio and FLOPS decrease, the portion of halo elements in the input tile increases.

- Small tile size has a negative impact on memory coalescing.

Thread Coarsening

The sparse nature of the stencil makes it less useful for shared memory tiling than convolution. We’ll use the thread coarsening technique to overcome the work done by each thread to calculate from one grid point to column grid point values. The aim is to serialize the parallel units of work into each thread and reduce the price of parallelism. The main advantages are:

- It increases the tile size without increasing the number of threads. However, the number of threads remains unchanged, which simplifies scheduling. For the original block size, the thread block size would be T3. However, the thread block size is reduced to T2 for the coarsened block size.

- The other advantage is that it does not require all planes of the input tile to be present in the shared memory. For example, when all the blocks are in shared memory, it would require 3 * T3 * 4 bytes of memory, while for the coarsened block will require 3 * T2 * 4 bytes of memory.

The kernel with thread coarsening in the z direction is given by:

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float* in, float* out, unsigned int N) {

int iStart = blockIdx.z*OUT_TILE_DIM; // z index of the output tile grid point

int j = blockIdx.y*OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.y - 1;

int k = blockIdx.x*OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.x - 1;

// loading each block into the shared memory

__shared__ float inPrev_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

__shared__ float inCurr_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

__shared__ float inNext_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

// 1st layer

if (iStart-1 >= 0 && iStart-1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inPrev_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[(iStart - 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

// 2nd layer

if (iStart >= 0 && iStart < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[iStart*N*N + j*N + k];

}

// all threads blocks will be processing in the x-y plane

// z index will be identical while processing this loop

for (int i = iStart; i < iStart + OUT_TILE_DIM; i++) {

// all thread blocks collaborate to load the third layer

if (i + 1 >= 0 && i + 1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = in[(i+1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

__syncthreads();

// calculating the output grid point value

if (i >= 1 && i < N-1 && j >= 1 && j < N-1 && k >= 1 && k < N-1) {

if (threadIdx.y >= 1 && threadIdx.y < IN_TILE_DIM - 1

&& threadIdx.x >= 1 && threadIdx.x < IN_TILE_DIM - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c1*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x-1]

+ c2*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x+1]

+ c3*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y+1][threadIdx.x]

+ c4*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y-1][threadIdx.x]

+ c5*inPrev_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x]

+ c6*inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

__syncthreads();

// moving to the next output plane for its calculation

inPrev_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inNext_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x];

}

}

Register Tiling

Previously, each inPrev_s and inNext_s element required only one thread to calculate the output tile grid point. Only inCurr_s elements are accessed by multiple threads, and hence, they truly need to be in shared memory; others can stay in the registers of the single-user thread. Therefore, we take advantage of the register tiling technique along with the thread coarsening. The computed output tile is stored in the registers of the blocks thread. Hence, coarsening and register tiling kernels have two major advantages over just coarsening kernels.

- Many reads and writes to the shared memory are shifted into the registers. Hence, the code runs faster.

- As mentioned earlier, each block consumes 1/3 of the shared memory, which leads to higher register usage. The programmers should consider this trade-off while writing the kernel.

Note that this register tiling with coarsening does not impact global memory bandwidth consumption.

__global__ void stencil_kernel(float* in, float* out, unsigned int N) {

int iStart = blockIdx.z*OUT_TILE_DIM;

int j = blockIdx.y*OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.y - 1;

int k = blockIdx.x*OUT_TILE_DIM + threadIdx.x - 1;

// creating three register variables

float inPrev;

float inCurr;

float inNext;

// only loading inCurr_s to the shared memory

// accessed by multiple threads, therefore, need not be in a shared memory

// shared memory accesses get reduced by 1/3

__shared__ float inCurr_s[IN_TILE_DIM][IN_TILE_DIM];

// calculation performed in the register variable

if (iStart-1 >= 0 && iStart-1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

inPrev = in[(iStart - 1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

if (iStart >= 0 && iStart < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

// calculation performed in the register variable

inCurr = in[iStart*N*N + j*N + k];

// maintains a copy of the current plane of the input tile in the shared memory

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inCurr;

}

for (int i = iStart; i < iStart + OUT_TILE_DIM; i++) {

if (i+1 >= 0 && i+1 < N && j >= 0 && j < N && k >= 0 && k < N) {

// calculation performed in the register variable

inNext = in[(i+1)*N*N + j*N + k];

}

__syncthreads();

if (i >= 1 && i < N-1 && j >= 1 && j < N-1 && k >= 1 && k < N-1) {

if (threadIdx.y >= 1 && threadIdx.y < IN_TILE_DIM - 1

&& threadIdx.x >= 1 && threadIdx.x < IN_TILE_DIM - 1) {

out[i*N*N + j*N + k] = c0*inCurr

+ c1*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x-1]

+ c2*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x+1]

+ c3*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y+1][threadIdx.x]

+ c4*inCurr_s[threadIdx.y-1][threadIdx.x]

+ c5*inPrev

+ c6*inNext;

}

}

__syncthreads();

// maintains a copy of the current plane of the input tile in the shared memory

inPrev = inCurr;

inCurr = inNext;

inCurr_s[threadIdx.y][threadIdx.x] = inNext_s;

}

}

Where to Go Next?

I hope you enjoyed reading this blog post! If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to drop a comment or reach out to me. I’d love to hear from you!

This post is part of an ongoing series on CUDA programming. I plan to continue this series and keep things exciting. Check out the rest of my CUDA blog series:

- Introduction to Parallel Programming and CPU-GPU Architectures

- Multidimensional Grids and Data

- Compute Architecture and Scheduling

- Memory Architecture and Data Locality

- Performance Considerations

- Convolution

- Stencil

- Parallel Histogram

- Reduction

Stay tuned for more!

Resources & References

1. Wen-mei W. Hwu, David B. Kirk, Izzat El Hajj, Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach, 4th edition, United States: Katey Birtcher; 2022

2. I used Excalidraw to draw the kernels.

Let me know what you think of this article on Twitter @khushi__411 or leave a comment below!