Parallel Histogram

Introduction

The aim of the blog posts is to introduce a parallel histogram pattern, where each output element can be updated by any thread. Therefore, we should coordinate among threads as they update the output value. In this blog post, we will read the introduction about using atomic operations to serialize the updates of each element. Then, we will study an optimization technique: privatization. Let’s dig in!

This blog post is written while reading the ninth chapter, Parallel Histogram: An Introduction to atomic operations and privatization, of the incredible book “Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach1” by Wen-mei W. Hwu, David B. Kirk, and Izzat El Hajj.

Atomic operations and a basic histogram kernel

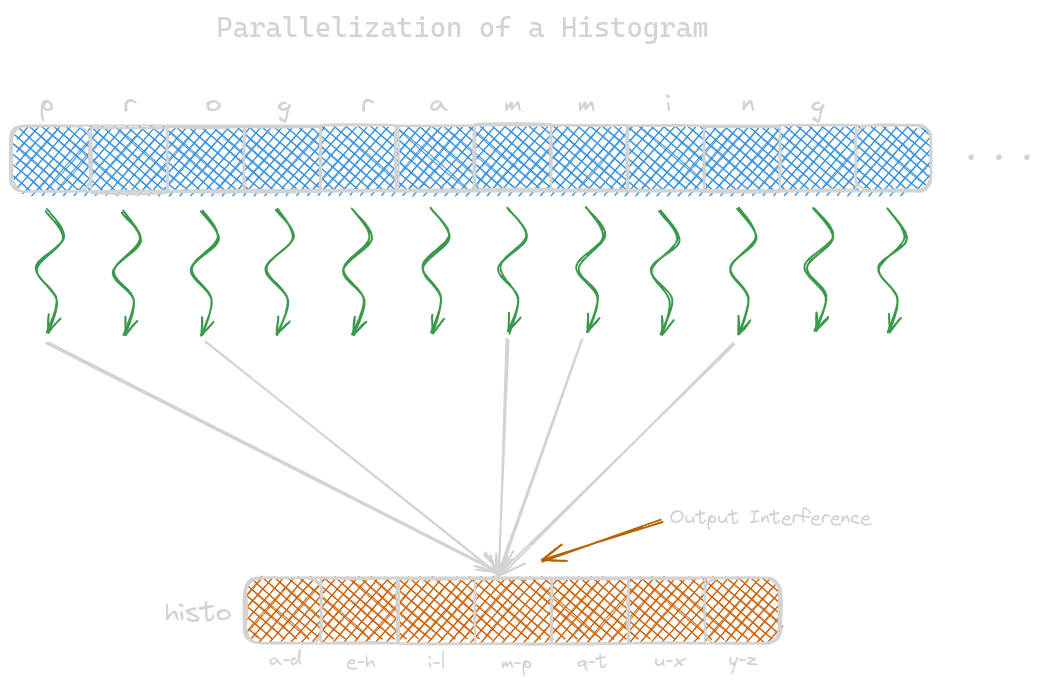

To parallelize histogram computation, launch the same number of threads as the number of data such that each thread has one input element. Each thread reads the assigned input and increments the appropriate counter. When multiple threads increase the same elements, it is known as output interference. Programmers should handle these race conditions and atomic operations. These operations perform read, write and modify. The undesirable outcomes caused are known as the read-modify-write race condition, i.e., when two or more threads compete to attain the same results.

An atomic operation on a memory location is an operation that performs a read-modify-write sequence on the memory location in such a way that no other read-modify-write sequence to the location can overlap with it. Read, modify, and write cannot be divided further; therefore named an atomic operation. Various atomic operations are addition, subtraction, increment, decrement, minimum, maximum, logical and, and logical or. To perform atomic add operation in CUDA:

// intrinsic function

int atomicAdd(int* address, int val);

Note that intrinsic functions are compiled into hardware atomic operation instructions. All major compilers support them.

A CUDA kernel performing a parallel histogram computation is given below:

__global__ void histo_kernel(char* data, unsigned int length, unsigned int* histo) {

// thread index calculation

unsigned int i = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

int alphabet_position = data[1] - 'a';

if (alphabet_position >= 0 && alphabet_position < 26) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[alphabet_position/4]), 1);

}

}

}

Latency and throughput of atomic operations

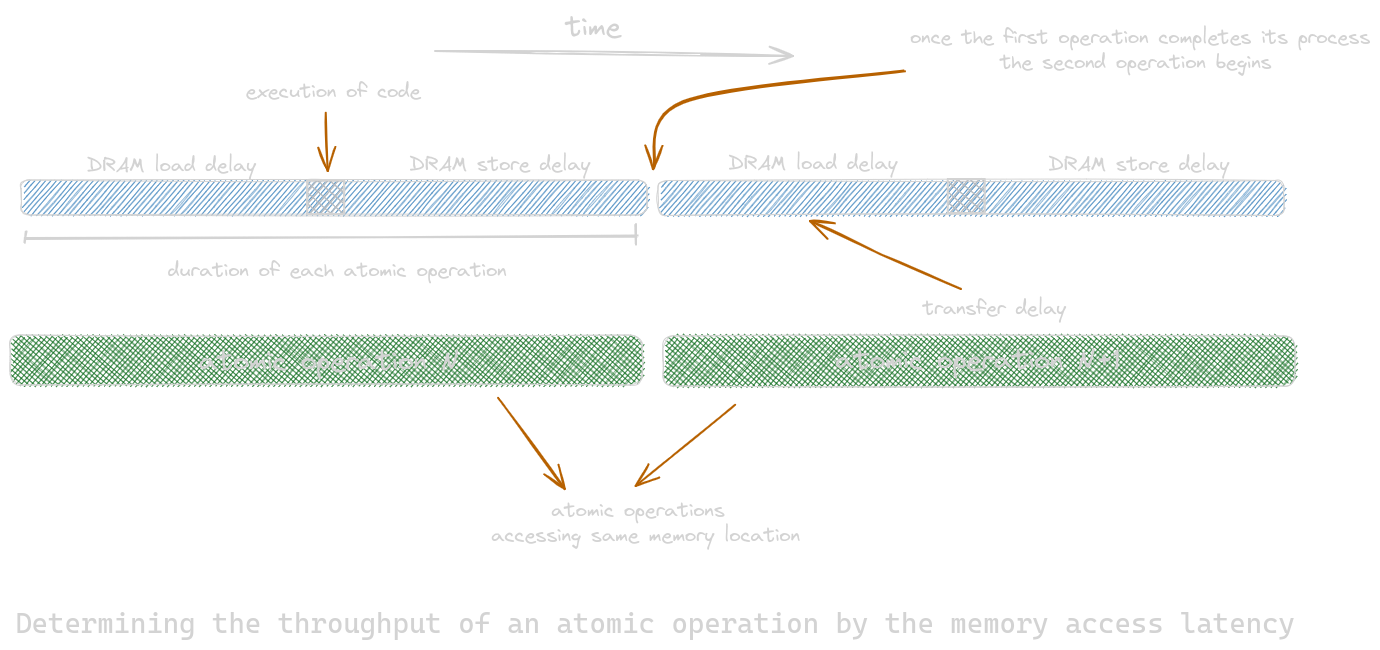

Note that it should be very clear that the many DRAM accesses result in high memory access throughput. This sometimes breaks down when atomic operations update the same memory location. This can be resolved by starting a new read-modify-write sequence once the previous read-modify-write-sequence is completed. Only one atomic operation executes at the same memory location at a time. This duration is approximately the latency of a memory load and the latency of a memory store. The length of these time sections is the minimum amount of time dedicated to each atomic operation. To improve the throughput of atomic operations, we could reduce the access latency to the heavily contended locations. Cache memories are primary tools to reduce memory access latency.

Privatization

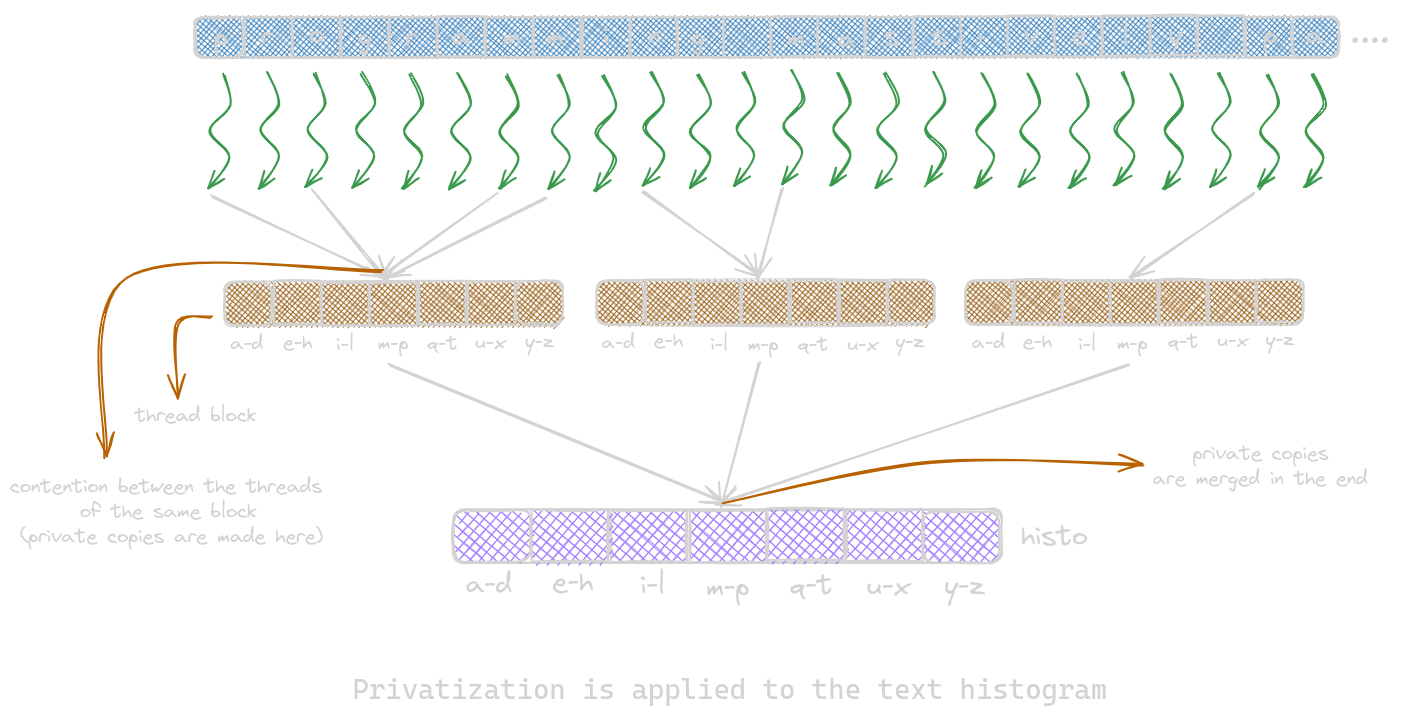

Privatization is the process of replicating output data into private copies so that each subset of threads can update its private copy. Its main benefits are low latency and increased throughput. However, the main downside is that the private copies need to be merged into the original data structure after the computation is completed. Therefore, privatization is done for a group of threads rather than individual threads.

// creates a private copy of the histogram for every block

// These private copies will be cached in the L2 cache memory

__global__ void histo_private_kernel(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *histo) {

unsigned int i = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

int alphabet_position = data[i] - 'a';

if (alphabet_position >= 0 && alphabet_position < 26) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[blockIdx.x*NUM_BINS + alphabet_position/4]), 1);

}

}

// commit the values in private copy into the block

if (blockIdx.x > 0) {

// To let threads wait for each other to finish updating the private copy

__syncthreads();

// responsible for creating one or more histogram bins

for (unsigned int bin=threadIdx.x; bin<NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = histo[blockIdx.x*NUM_BINS + bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[bin]), binValue);

}

}

}

}

If the number of bins in the histogram is small, the private copy can be declared in the shared memory. But the problem is we cannot access multiple blocks because the blocks do not share visibility in the shared memory. However, the latency of the data is reduced while placing data in shared memory. As discussed above, the reduction in latency leads to improved throughput of the atomic operations. The histogram kernel using shared memory allocation:

// creates a private copy of the histogram for every block

// These private copies will be cached in the L2 cache memory

__global__ void histo_private_kernel(char *data, unsigned int length, unsigned int *histo) {

// privatized bins in shared memory

__shared__ unsigned int histo_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

histo_s[bin] = 0u;

}

__syncthreads();

unsigned int i = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

if (i < length) {

int alphabet_position = data[i] - 'a';

if (alphabet_position >= 0 && alphabet_position < 26) {

atomicAdd(&(histo_s[alphabet_position/4]), 1);

}

}

// commit the values in private copy into the block

__syncthreads();

// responsible for creating one or more histogram bins

for (unsigned int bin=threadIdx.x; bin<NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

// read private bin value

unsigned int binValue = histo_s[bin];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[bin]), binValue);

}

}

}

Coarsening

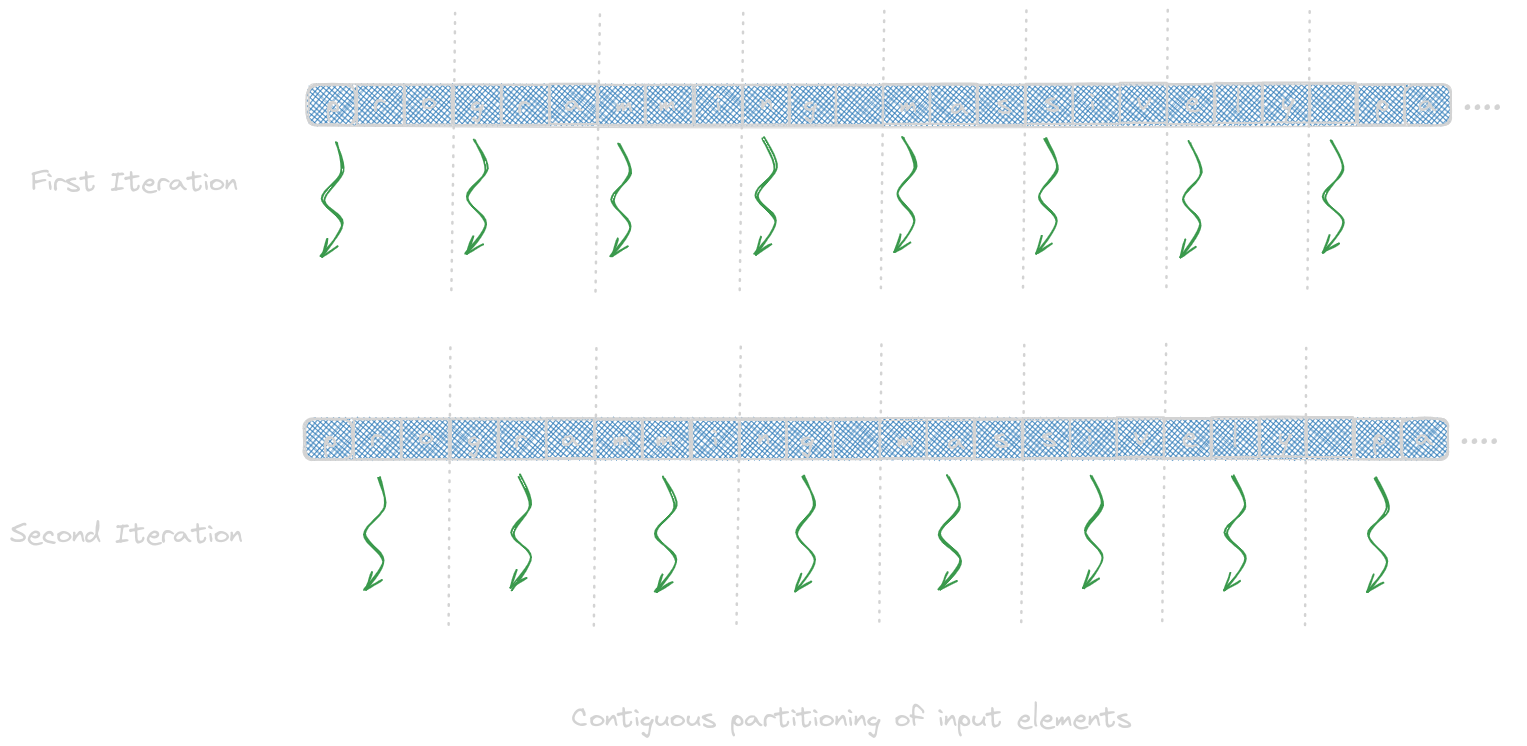

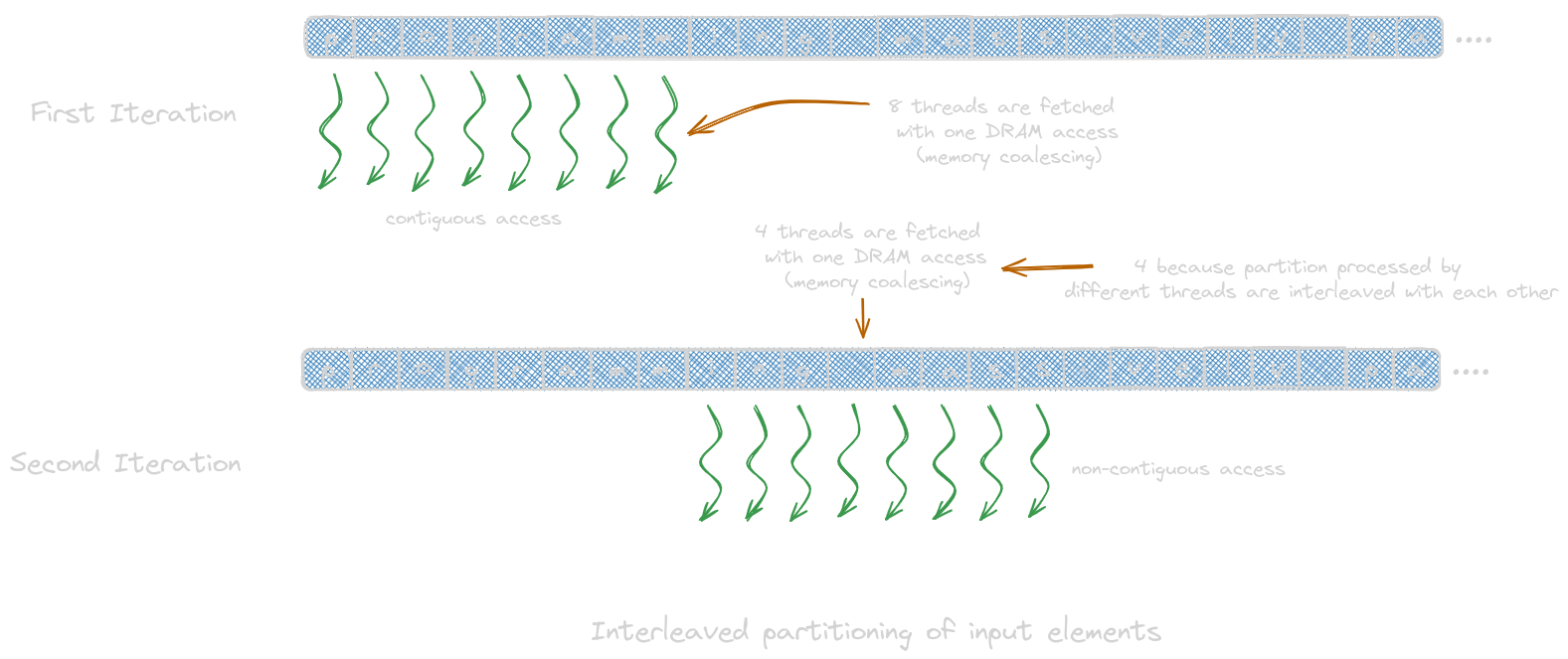

As discussed above, shared memory reduces the latency of each atomic operation in the privatized histogram. But their is an extra overhead while making the private copy to the public copy. This is done once per thread block. This overhead is worth paying when we execute thread blocks in parallel. But when the number of thread blocks that are launched exceeds the number that can be executed by the hardware, there is unnecessary privatization overhead. This overhead can be reduced via thread coarsening, i.e., by reducing the number of private copies made and by reducing the number of blocks such that each thread processes multiple input elements. We’ll read two ways to assign multiple input elements to a thread:

- Contiguous Partitioning: sequential access pattern by each thread makes good use of cache lines.

- Interleaved Partitioning: partitions processed by the different threads are interleaved with each other.

Contiguous Partitioning

__global__ void histo_private_kernel(char* data, unsigned int length, unsigned int* histo) {

// initialize private bins

__shared__ unsigned int histo_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

histo_s[binIdx] = 0u;

}

__syncthreads();

// histogram

// Contiguous partitioning

// CFACTOR is a coarsening factor

unsigned int tid = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

for (unsigned int i = tid*CFACTOR; i < min((tid+1)*CFACTOR, length); i++) {

int alphabet_position = data[i] - 'a';

if (alphabet_position >= 0 && alphabet_position < 26) {

atomicAdd(&(histo_s[alphabet_position/4]), 1);

}

}

__syncthreads();

// commit to global memory

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = histo_s[binIdx];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[binIdx]), binValue);

}

}

}

Interleaved Partitioning

__global__ void histo_private_kernel(char* data, unsigned int length, unsigned int* histo) {

// initialize private bins

__shared__ unsigned int histo_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

histo_s[binIdx] = 0u;

}

__syncthreads();

// histogram

// Interleaved partitioning

unsigned int tid = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

for (unsigned int i = tid; i < length; i += blockDim.x*gridDim.x) {

int alphabet_position = data[i] - 'a';

if (alphabet_position >= 0 && alphabet_position < 26) {

atomicAdd(&(histo_s[alphabet_position/4]), 1);

}

}

__syncthreads();

// commit to global memory

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = histo_s[binIdx];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[binIdx]), binValue);

}

}

}

Aggregation

Datasets have many identical data values in some areas. Such datasets use each thread to aggregate consecutive updates into a single update if they update the same element of the histogram. These updates reduce the number of atomic operations, thus improving the throughput of the computation. An aggregated kernel requires more statements and variables. Thus, if the data distribution has many atomic operation executions, the aggregation leads to higher speed.

__global__ void histo_private_kernel(char* data, unsigned int length, unsigned int* histo) {

// initialize privatized bins

__shared__ unsigned int histo_s[NUM_BINS];

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

histo_s[bin] = 0u;

}

__syncthreads();

// histogram

// to keep track of the number of updates aggregated

unsigned int accumulator = 0;

// tracks the index of the histogram bin

int prevBinIdx = -1;

unsigned int tid = blockIdx.x*blockDim.x + threadIdx.x;

for (unsigned int i = tid; i < length; i += blockDim.x*gridDim.x) {

int alphabet_position = data[i] - 'a';

if (alphabet_position >= 0 &&alphabet_position < 26) {

int bin = alphabet_position/4;

if (bin == prevBinIdx) {

++accumulator;

} else {

if (accumulator > 0) {

atomicAdd(&(histo_s[prevBinIdx]), accumulator);

}

accumulator = 1;

prevBinIdx = bin;

}

}

}

__syncthreads();

// commit to global memory

for (unsigned int bin = threadIdx.x; bin < NUM_BINS; bin += blockDim.x) {

unsigned int binValue = histo_s[binIdx];

if (binValue > 0) {

atomicAdd(&(histo[bin]), binValue);

}

}

}

Where to Go Next?

I hope you enjoyed reading this blog post! If you have any questions or suggestions, please feel free to drop a comment or reach out to me. I’d love to hear from you!

This post is part of an ongoing series on CUDA programming. I plan to continue this series and keep things exciting. Check out the rest of my CUDA blog series:

- Introduction to Parallel Programming and CPU-GPU Architectures

- Multidimensional Grids and Data

- Compute Architecture and Scheduling

- Memory Architecture and Data Locality

- Performance Considerations

- Convolution

- Stencil

- Parallel Histogram

- Reduction

Stay tuned for more!

Resources & References

1. Wen-mei W. Hwu, David B. Kirk, Izzat El Hajj, Programming Massively Parallel Processors: A Hands-on Approach, 4th edition, United States: Katey Birtcher; 2022

2. I used Excalidraw to draw the kernels.

Let me know what you think of this article on Twitter @khushi__411 or leave a comment below!